In the arid expanse of northwestern Kenya, the Kakuma refugee camp has grown into a sprawling community of more than 300,000 displaced individuals from over 20 countries. Originally established in 1992 to shelter young people fleeing the war in Sudan, the refugee camp is the largest in Africa, covering about 15 sq miles (40 km), with residents from South Sudan, Somalia, and other neighboring countries.

For years, the refugee camp’s maps were severely outdated—hindering aid delivery, infrastructure planning, and emergency response. The camp’s irregular layout and diverse shelter types made traditional mapping methods difficult. But this challenge sparked a remarkable collaboration that redefined what humanitarian tech could achieve.

“I think collaboration was key because each person brought something unique to the table,” says Dr. Simone Fobi Nsutezo, Applied Research Scientist, Microsoft AI for Good Lab.

At the heart of the collaboration to update the Kakuma refugee camp’s mapping system, a triad of innovation was fundamental. Each partner brought something unique to the table, and together, they created real impact. UNHCR’s Hive—the UN Refugee Agency’s innovation lab—defined the issues the refugee camp was facing while The Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT) provided essential on-the-ground data collection and vital community integration.

Amplifying impact through community engagement

The guiding forces were a desire to do work that truly mattered, a passion for remote sensing and satellite imagery, and the goal of meeting refugees’ needs. Manual mapping, while valuable, was slow and labor-intensive, but the Microsoft AI for Good Lab team saw an opportunity for AI and machine learning to help give human mappers the tools they needed.

“Once you’ve trained a model on a small amount of data, it’s very fast to get predictions on new areas. We have open-source code for mapping solar panels, buildings, roof types, sanitation facilities, and anyone can independently use it,” says Dr. Amrita Gupta, Applied Research Scientist, Microsoft AI for Good Research Lab.

To better understand on‑the‑ground conditions, the HOT mapping team documented visible indicators of electricity access—such as solar panels and power lines present in the camp. While most electricity is self‑generated at individual buildings, this information helped create a clearer picture of where essential services could realistically operate, and highlighted gaps in the broader infrastructure landscape.

The goal was to help the camp feel less like a temporary shelter and more like a permanent settlement. Mapping was the first step toward ensuring the project remained grounded in humanitarian needs. The project’s commitment to open access meant that all data and imagery generated would be freely available. This amplified the reach beyond Kakuma, championing refugee inclusion.

More stories

-

HOT worked with residents who owned the mapping process.

-

Models were trained to identify features like solar panels.

-

Residents and AI experts collaborated to define Kakuma’s unique structures.

It is all the community. We didn’t forget anyone.

Akso Kaposho Mupenzi

Map contributor and refugee

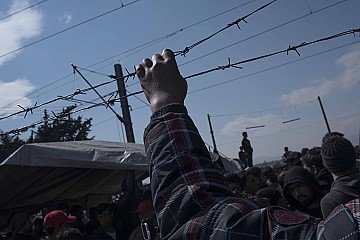

By operating on the ground in Kenya, the HOT team brought the human touch. The actual data collection activity was entirely led by locals, from introducing the project to flying the drones, and refugees in the camp helped manually identify features in the area. HOT teams flew drones to capture high-resolution aerial imagery and conduct field validation with refugee mappers. But most importantly, they trained and empowered members of the refugee camp—turning data collection into community engagement.

Refugees became mappers, interpreters, and stewards of their own environment, creating ground truth data. Their local knowledge added depth and accuracy, giving them ownership of the process. HOT’s team manually tagged 10 sq miles (16 km²) of imagery, creating a rich training dataset for AI development that can be kept current as the camp evolves.

“AI was primarily used for pattern matching and time saving. It helped us find signals in the data that would be hard to spot manually,” says Dr. Gupta.

Drawing on the rich, community-tagged imagery collected in the refugee camp, Microsoft’s AI for Good Lab developed advanced machine learning models using Azure cloud services. These models were trained to accurately identify a wide range of features—buildings, sanitation blocks, solar panels of streetlights and rooftops, and elements of the power network like poles and lines—reflecting the camp’s diverse and irregular landscape.

By leveraging both local expertise and AI, the team was able to overcome the challenges posed by the refugee camp’s unique structures, enabling rapid analysis and pattern recognition that would be difficult to achieve manually. All models and datasets were released as open source on GitHub, empowering developers, researchers, and humanitarian organizations worldwide to build on this work and adapt it for other communities in need.

A testament to possibilities

This open-source mapping project demonstrates how collaboration can help establish a strong foundation for sustainable development. As the town of Kakuma’s municipal boundaries have evolved, accurate spatial data has become critical for long‑term planning and service delivery across the town and surrounding settlements—ensuring any future annexation or integration decisions are grounded in reality.

GitHub is where the next chapter of this project begins—connecting developers, civic technologists, and data scientists to real-world humanitarian challenges. And everything learned has become part of a global knowledge base for assisting refugees. By sharing this code openly, anyone, anywhere, can build on it, improve it, and use it to make a difference. The story of the Kakuma refugee camp is evidence of what’s possible when humanitarian vision meets innovation.

No one knows a community better than the people living there. AI didn’t replace them, but expanded their capabilities.

Juan M. Lavista Ferres

Lab Director AI For Good Lab, Microsoft